Announced at last year’s Daytona 500, Toyota’s decision to bring a four-cylinder variant of the Supra to the U.S. market is good news for anyone who wants more choice in the sports car market. The BMW-based entry-level car gets a 255-hp turbocharged engine and is 200 lbs lighter than the straight-six variant. Underneath, it’s basically a Z4 sDrive30i, which sounds like some sort of inkjet printer. Supra’s a better name. But isn’t a four-cylinder Toyota sports car actually a Celica?

Turning 50 years old in 2020, the humble Celica finds itself briefly touched on in any history of its big brother, then passed right over. There’s a brief mention of the Celica Supra, a long-nosed, six-cylinder GT, then some hurried flipping forward until turbocharging shows up and things get good. That’s a shame, because the history of the Celica is arguably more important, and certainly more interesting, than that of the Supra.

As a car, the Celica is a historical record, a snapshot of the time it lived in. Celicas have variously been rear-wheel, front-wheel, and all-wheel drive. They’ve contested world rally championships, taken podiums in IMSA for the likes of Dan Gurney, and been the backbone of a single-make racing series that Carlton from Fresh Prince of Bel-Air won three times.

While there’s no current model that wears the name, past generations of the Celica include affordable classics, tantalizing forbidden fruit, and overlooked performers. If Toyota wanted to bring the nameplate back—and there are rumors it does—it’d have to do better than a rebadged BMW coupe. The Celica isn’t just a four-cylinder Supra. It’s better than that.

Toyota’s pony car

To begin with some pedantic quibbling, the Celica was never a sports car, nor was it Toyota’s first affordable sporting machine. That honor goes to the little Toyota Sports 800, the Yota-hachi, a tiny car of such endearing weirdness that it could have been a Citroën.

The first Celica, which replaced the Yota-hachi in Toyota’s lineup, was a far less odd and toy-like proposition. In fact, it was a copy of an already successful idea. If the Datsun 510 was the poor man’s BMW 2002, then the Celica was a thrifty alternative to the Mustang and Camaro.

It was a pony car. Based on the architecture of the Toyota Carina sedan, slightly larger than a Corolla, the first generation Celica had coke-bottle styling and a 2+2 layout that was very familiar to American buyers, in a scaled-down package. The later lift-back models doubled down on the Mustang resemblance, with vertical-bar taillights and louvers on the C-pillars.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the Japanese automotive industry produced cute, quirky, and largely disposable machinery that few took seriously. In contrast, the Celica ST (chassis code RA20) that arrived in North America in 1970 was a thoroughly modern product, one of the first Japanese cars assembled using robots. It had four-wheel independent suspension with disc brakes up front, a multilink rear, and standard radial tires. Its badge featured a celestial dragon boat, fitted with two star-embossed sails, indicating that it could sail through the heavens.

In factory tune, neither the looks nor the badge were backed up by much actual performance. Cornering grip was average at best and, with less than 100 hp on offer, the Celica’s SOHC four-cylinder powertrain was better suited to commuting rather than straight-line speed. Japanese-market engine options were slightly better (as usual) with the hottest DOHC 2.0-liter variant making nearly 145 hp.

Still, factory-backed racing efforts buoyed the Celica’s reputation even as backyard tuners fitted bigger wheels to get more grip in the corners. Celicas won various racing events in Asia, and Swedish driver Ove Andersson took his Celica 1600GT to several class wins in European touring car racing. But it’s best to finish the first Celica’s story with the absolutely bonkers Celica LB Turbo.

Based on the lift-back GT model, the LB Turbo was a Group 5 racing car built in 1977 by Schnitzer Motorsport. Fitted with enormous fiberglass flares, it had a huge KKK turbocharger and an intercooler the size of a dishwasher. Power from the 2090-cc four-cylinder was a ridiculous 560 hp, making the little Celica a genuine rival to the Porsche 935s it tilted against. Driven by Harald Ertl, it managed a best fourth-place finish in regular competition, and won a non-championship race at Zolder. It would not be the last heavy-hitter Celica.

The forgotten years and the King of Africa

Launched in the 1978 model year, the second-generation Celica was designed in California, and had all the sporting intent of a Jello salad. Yes, it would give rise to the Celica Supra, with a longer hood to accommodate a smooth inline-six engine, but there’s not much here to get excited over. Toyota eventually stuffed a 2.4-liter pickup truck engine in the nose, coupled to a four-speed automatic transmission. Snore.

By 1981, even Toyota appeared bored. The third-generation Celica arrived with available rack-and-pinion steering and better engine choices for the U.S. market. Pick of the bunch was the Celica GT-S, which, while not quite as lastingly cool as the contemporary Mk II Supra, married available fender flares and big wheels with affordable fuel economy. Today, both the second- and third-generation cars are uncommon sights on the road.

The third-generation car marked the first WRC win for the Celica nameplate and the creation of a minor rally legend. Built on the bones of a Japan-only homologation special, the Celica Twincam Turbo was a Group B car that was outclassed on paper, but dominant in the field. Rear-drive only, and with as much as 380 hp from its turbocharged 2.1-liter four-cylinder engine, it still couldn’t quite keep up with all-wheel-drive rivals on the tighter European stages.

Yet the Celica was tough and simple, and that meant safari rally success. From 1984 to 1986, the Twincam Turbo swept the Kenyan Safari Rallies. A further three wins in Western African rallying were added to the trophy cabinet in the hands of Finnish driver Juha Kankkunen and Swede Björn Waldegård. Onlookers started calling the car The King of Africa.

Group B rallying would end in 1987, and big changes were afoot for the Celica. However, its rallying days were far from over.

The all-American Celica

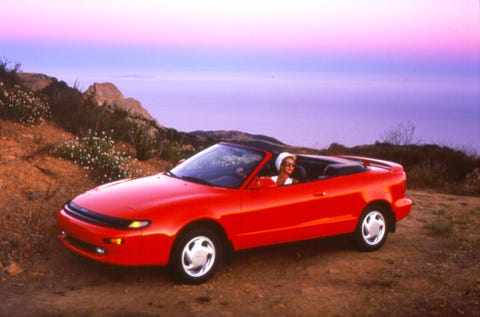

In its fourth generation, the Celica changed entirely. On the plus side, it no longer suffered from inevitable comparisons to the more powerful, better-equipped Supra. Less good, at least to the purist, was that the Celica was now a front-wheel-drive compact.

Still, there were positives. The mid-1980s were a high point for hot hatchbacks and their siblings, and the Celica GT-S was a whippy little scrapper, light on its feet if not overpowered at 135 hp. The lift-back variant added practicality to coupe styling, and there was an impressive feature load-out.

For Toyota fans who’d cheered the Twincam Turbo Celica’s wins from afar, Toyota also offered something to appease American rally fans. Decades before the Subaru WRX arrived on our shores, the Celica Turbo All-Trac featured a 190 hp 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine, a five-speed gearbox and all-wheel-drive with a viscous center differential coupling. The All-Trac didn’t fully arrive until 1988, but one year earlier, 77 special editions—one for each Toyota dealership in the U.S.—led the way, every one of them inscribed with “IMSA GTO Champion” on its flanks.

The IMSA champion these first 77 were named for was the All-American Racing Celica GTO. Founded by Dan Gurney and Carroll Shelby, AAR was contracted by Toyota in 1983 to compete in GT racing, and by 1986 was ready to campaign their Celica in the GTO class.

The three Celica GTOs built were wild machines, with a wide aerodynamic body penned by Hiro Fujimori, who had previously worked for Japan’s Dome racing. A tube-frame racer built around the general shape of the Celica, it featured a 2.1-liter turbocharged engine capable of above 600 hp, but restricted to 450 in racing trim. Top speed was 195 mph, and the GTO wore the classic red-orange-yellow Toyota racing livery with pride.

It won the 1987 IMSA Championship by the thinnest of margins, clinching the GTO class with a final race victory over the nearest Mustang rival by little more than a car length. Later, AAR would apply the knowledge learned from the Celica GTO to the GTP class with the hugely dominant Eagle Mk III.

Cheat codes and Castrol

Meanwhile, back in the world of rally, turbocharged, all-wheel-drive Celica variants were building a winning reputation. Things began with the third generation All-Track, called the GT-Four in most markets outside the U.S., or the ST165 to Toyota diehards.

Nine of the 13 WRC wins racked up by the ST165 came with Spaniard Carlos Sainz (father of the current F1 driver of the same name) at the wheel. Sainz won the driver’s title in 1990 and 1992, and in 1993 and 1994 Toyota would take the WRC manufacturer’s title with the follow-up ST185 chassis. The third iteration ST205 proved itself a winner too—at any cost.

Most gearheads of a certain age remember these gravel-slinging Celicas in digital format. Thanks to the sit-down Sega Rally cabinet, a mainstay of any 1990s arcade, hucking red-and-green Castrol-liveried Celicas into the underbrush was within the grasp of anyone with a fistful of quarters. In the days before streaming video shrank the world, Toyota’s far-off WRC successes reached a new youth market.

The homologation specials built to put Toyota on the podium are just now becoming importable under U.S. 25-year law, and they’re pretty special. In the Japanese market, power from the 2.0-liter turbocharged inline-four was above 250 hp, making this sixth-generation car the most powerful production Celica ever built.

However, the hottest-ever Celica would get Toyota’s fingers burned when the team got a little greedy (allegedly). At the 1995 Rally de Catalunya, with a fourth championship victory on the horizon, scrutineers discovered that the mighty Toyota had an ace up its sleeve.

Like most rally cars, a restrictor plate on the turbocharged Celica’s engine strangled airflow to keep horsepower levels in check. However, when the plate was actually bolted on and tightened down, the clamps would open up a tiny 0.2-inch fracture. The space was enough to let the turbocharger gulp down enough air for a 50-hp bump.

Toyota claimed innocence, but the FIA stripped the team of its points, and handed out a one-year ban. Instead, the 1995 WRC championship went to a young Scot named Colin McRae and his blue Subaru Impreza.

An overlooked gem and the road ahead

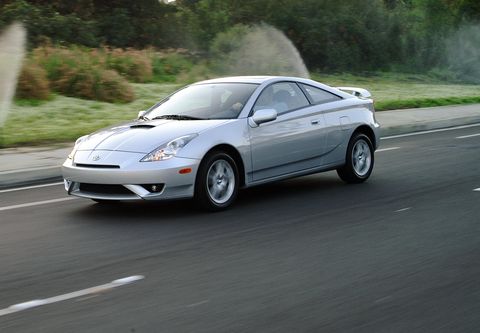

The seventh and last generation of the Celica arrived at the tail end of the 1990s bearing evidence of Toyota’s efforts to return the nameplate to its economical roots. There was to be no more turbocharged complexity, but rather a focus on simplicity and affordability.

Having said that, the last of the Celicas was in some ways the best. The GT-S variant came with the 2ZZ-GE engine, a high-revving 1.8-liter four-cylinder that made 180 hp and was potent enough for Lotus to stuff it into the Elise.

Initially, the revvy little Celica was a success for Toyota, but sales tailed off sharply towards the end of its run. It remains an overlooked bargain if you can find a well-kept one, and still maintains some lift-back practicality. Slightly tweaked versions were used for Toyota’s Pro/Celebrity race, which ran until 2016 before the Long Beach Grand Prix. The last winner was Alfonso Ribeiro, a.k.a. Carlton from Fresh Prince.

The Scion tC is considered by many to be a Celica in all but name. It wasn’t all that quick in most trims, but offered a dose of style and practicality that adhered to the Celica ethos.

As for the four-cylinder Supra, no, it’s not really a Celica descendant. As a reworked BMW product, it’s too complex and too expensive to live with. As a two-seater, it’s just not pragmatic enough.

If Toyota did want to bring back the Celica, it would have to be built on the bones of the Corolla and the Yaris GR. Renderings already exist of the current Corolla as a coupe variant, and a two-door powered by a 250-plus-hp 1.6-liter three-cylinder engine would split the difference between a Civic Si coupe and a Subaru WRX, and nicely fit the original Celica’s mission parameters. It’s fun to dream of a rear-drive production car that might deliver what Nissan’s IDX concept promised, but a reborn Celica would have to contend with market realities.

Dedicated sports cars are a hard sell these days. They require too much specialized engineering, and are often priced accordingly. But sporty compacts like the Celica, built using parts already at hand and with an eye towards everyday livability, provide joy that’s accessible to ordinary enthusiasts.

If there’s room in the market for a four-cylinder Supra, there’s room for a lighter, sportier, coupe version of the Corolla. In a future where drivers are likely to be measuring the value of every dollar they spend, a return to celestial performance that’s within reach would be welcome.

More Stories

Australia’s 4×4 Aftermarket Wheels: Embracing Performance, Style, and Adventure

Top Of the Line Amplifier – Pioneer Premier Series – PRS-A900 Review

5 Signs That It’s Time For An Engine Checkup